The disconnect between joined-up care and reality

Healthcare systems worldwide consistently affirm that every patient deserves joined-up, person-centred care. However, despite the rhetoric, patient records remain fragmented, scattered across disconnected systems, inaccessible to clinicians who need them, and invisible to patients.

This is not merely a technical inconvenience. It’s a structural failure that undermines safety, efficiency, and the overall quality of care.

Why fragmented records pose real risks

Over a lifetime, patients interact with a broad range of services, including general practice, hospitals, aged care, community and social services, pharmacies, and more. Each of these touchpoints generates data, but too often, that data is trapped in siloed systems.

When vital information fails to follow the patient, clinicians are left in the dark, forced to make decisions without access to a patient’s medical history, test results, or current treatment plans. The consequences are significant:

- Duplicated tests and imaging

- Medication errors

- Delayed or inappropriate care

- Avoidable hospital admissions

Evidence underscores these risks. One review found that community-based Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) were consistently linked to fewer duplicated procedures, lower healthcare costs, and improved outcomes, especially when data was exchanged across organisational boundaries, not just within single systems.

The many names of Shared Care Records

Globally, the concept of Shared Care Records is implemented under various terms. While the function, longitudinal, cross-sector access to a patient’s health data, is consistent, terminology varies depending on the country, programme, and digital maturity.

Below is a categorised summary of commonly used terms and equivalents across the OECD, as seen in key health policy documents from the UK, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, the Netherlands, Australia, and Canada:

| Term | Description | Commonly used in |

| Shared Care Record (SCR) | Unified health record shared across care providers | England (NHS), New Zealand (in some districts) |

| Integrated Care Record | Focuses on linking health and social care records | UK regions, Canada (provincial pilots) |

| Electronic Health Record (EHR) | Patient-level digital medical record across providers; often more clinical than systemwide | United States, EU, Australia |

| Electronic Medical Record (EMR) | Digital version of a paper chart, usually within one organisation | Global term; limited interoperability |

| Health Information Exchange (HIE) | Infrastructure for sharing health data across organisations and systems | United States, some EU states |

| National Health Record | Countrywide longitudinal patient record | Denmark, Estonia, Finland |

| My Health Record | Personal digital health record controlled by patients | Australia |

| Citizen Health Portal/ Personal Health Record (PHR) | Patient facing record access; may include upload/input by user | Netherlands, Canada, Sweden |

| Interoperable Health Record | Describes records that are accessible across systems and vendors | Global policy frameworks (WHO, EU) |

| Continuity of Care Record (CCR) | Designed for transitions between providers | US (historically), some global standards |

| One Health Record/ One Patient, One Record | Policy or slogan implying unified record access | UK policy documents |

Sources: England – Fit for the Future: 10-Year Health Plan, England – Future State of Health and Healthcare in 2035, Denmark – Digital Health Strategy, Estonia – National Health Plan 2020–2030, Germany – Hospital Reform Article, Netherlands – Dutch Global Health Strategy 2023–2030, Australia – Long-Term National Health Plan, Canada – HealthCareCAN Strategic Plan

The promise of interoperable records

International policy has long recognised the value of interoperability. For example, the Shared Care Record programme aims to enable real-time clinical data exchange across settings and organisations in the UK. These consolidated records can include:

- Medications

- Diagnoses

- Allergies

- Treatment plans

- Social and environmental context

This information is critical to delivering safe, effective, and person-centred care.

Yet despite this clear direction, implementation remains uneven. Some regions lack full participation. Others have technical infrastructure in place but struggle with clinical uptake. Interoperability standards are improving, but are still inconsistent. Consent models also vary, further complicating access.

The result? A patchwork of systems where comprehensive, longitudinal patient records are still the exception, not the rule.

Barriers beyond technology

The barriers to interoperability are not just technical; they’re institutional, cultural, and contractual. Common issues include:

- Commercial concerns: Some providers see data sharing as a business risk.

- Workflow disruption: Systems that aren’t well integrated can slow down care.

- Data governance uncertainty: Ambiguity over who’s responsible for what.

- Lack of patient awareness: Patients often don’t understand how their data is shared, or not shared.

This lack of trust weakens consent and engagement.

It’s also important to recognise that not all data sharing models are equal. Community HIEs, which are built to span diverse organisations, have proven more effective than vendor-mediated systems confined to a single technology ecosystem. However, these models require strong governance, sustained funding, and long-term commitment, not just platform procurement.

The case for action: What Shared Care Records enable

The failure to unify patient records represents a missed opportunity to provide better, safer, more equitable care. But when implemented well, Shared Care Records can:

- Support faster diagnoses

- Improve medication safety

- Enhance long-term condition management

- Enable more effective urgent and emergency care

- Reduce administrative burden

- Support population-level planning and service design

These benefits are not automatic. They rely on:

- Widespread clinical adoption

- Consistent, open standards

- Robust privacy and consent frameworks

- Cultural alignment and commitment

It’s time the system stopped viewing data sharing as optional and started treating it as essential.

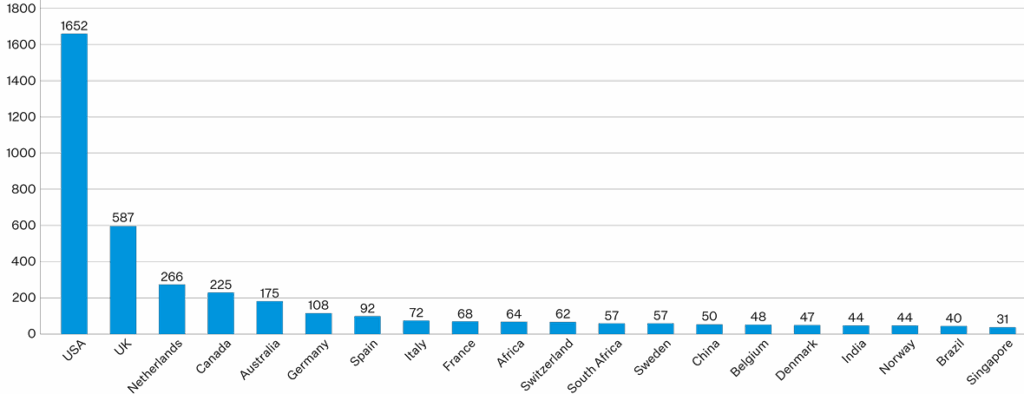

Source: International Journal of Integrated Care

This graph highlights the global leaders in integrated care research, with the USA, UK, and Netherlands topping the list. Their strong publication output reflects national focus on advancing joined-up care—demonstrating how evidence-based practice, policy, and technology go hand in hand.

It reinforces the case that countries making the greatest strides in Shared Care Records are also those investing in system-wide learning, research, and implementation. To realise the full benefits of shared records, healthcare systems must follow their lead: align strategy, fund innovation, and scale what works.

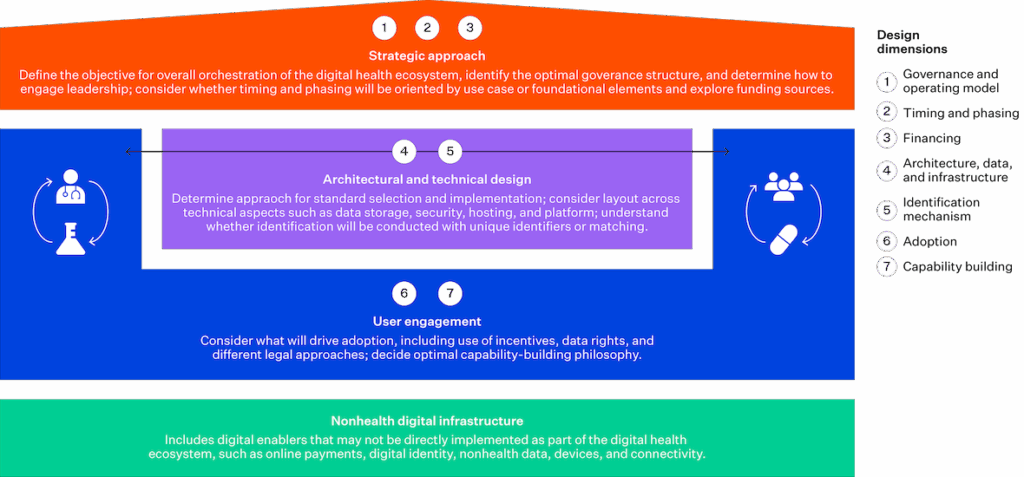

Building on that, the framework below outlines the critical design decisions countries must make when developing interoperable health systems, governance, infrastructure, financing, consent models, and user adoption.

Together, these graphs show that achieving the benefits of Shared Care Records isn’t just a technical project; it requires a strategic, evidence-informed system transformation.

Source: McKinsey & Company

Joined-up care is a clinical and moral imperative

If we genuinely believe in joined-up care, fragmented health records are no longer defensible. Policymakers, vendors, and providers must move beyond aspirational statements and directly tackle the inertia and complexity that stand in the way.

Patients don’t experience their health journeys in silos. Their records shouldn’t be siloed either.

Ready to deliver on the promise of integrated care?

Learn how Orion Health’s interoperable solutions support connected, person-centred care.

Authored by Tom Varghese, Global Product Marketing & Growth Manager at Orion Health.

References:

HETT Insights. (2024, January 23). Transforming healthcare in the UK: Unveiling the role, governance, and benefits of Shared Care Records. HETT Show Blog. https://blog.hettshow.co.uk/role-governance-and-benefits-of-shared-care-records

Kaelber, D. C., & Bates, D. W. (2007). Health Information Exchange and patient safety. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 40(6 Suppl), S40–S45. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/issue/health-information-exchange-and-patient-safety

McKinsey & Company. (2023). Building interoperable healthcare systems: One size doesn’t fit all. https://www.mckinsey.com/mhi/our-insights/building-interoperable-healthcare-systems-one-size-doesnt-fit-all

Menachemi, N., Rahurkar, S., Harle, C. A., & Vest, J. R. (2018). The benefits of Health Information Exchange: An updated systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(9), 1259–1265. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy035

Ong, T. (2018). Top 20 countries of publication for integrated care literature in PubMed. International Journal of Integrated Care, 18(2), A203. https://ijic.org/articles/3975/files/submission/proof/3975-1-15272-1-10-20180817.pdf