“I just can’t trust the data that might come in”

“I don’t want a barrage of e-mails coming in via patient mail, we won’t cope, we can’t cope now!”

“There’s a real nervousness about this, what happens if we don’t act and we’re liable?”

“This is all well and good, but quite frankly, my mother could never use an iPad”

“We’re going to end up with many patient portals, it feels too complicated”

Oh dear, we’re never going to make it, are we?

The future vision paints a picture of the citizen as an omnipresent part of the care team, self caring and managing, plugged into their record. Real time monitoring, open API’s exchanging data with innovative apps, people selecting those they will choose to help them manage their lives and wellbeing. Precision care. Beautiful. Useful goals, alerts and motivational tools can be set up in accordance with a condition, helping to prevent acute admissions or exacerbations of a condition. Software as a drug, even, where your best outcome is based on the a package of software and supportive tools tailored to you – more economically effective than the alternatives? Who knows, but interesting debate fodder.

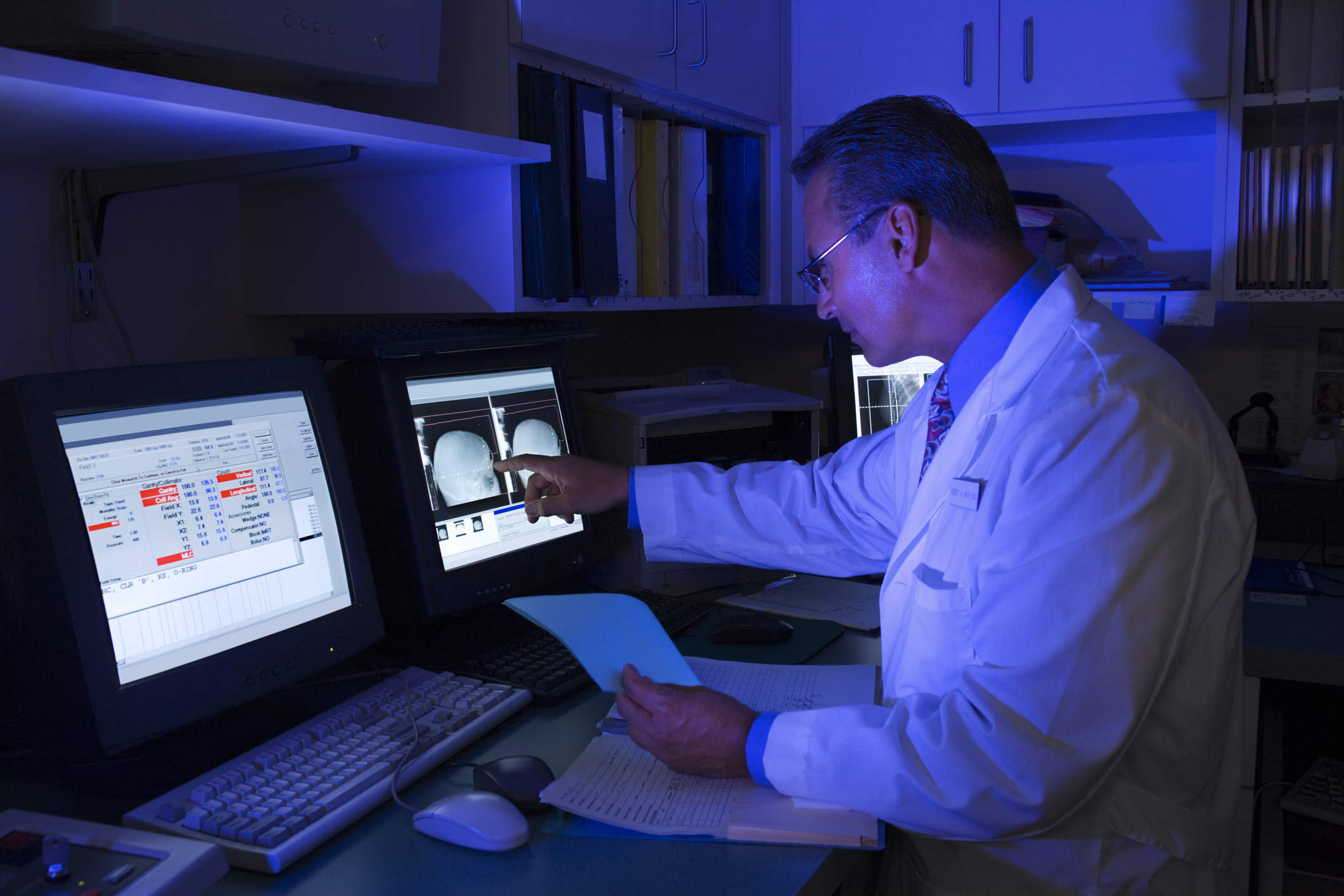

All this is half a world away, surely? Well, not so, things are moving. We all know that appointments and repeat prescriptions are available online. Chatting to a GP recently the view from the consultation room was also quite enlightening and encouraging. The picture painted was one where the production of an iPhone mid consultation was not out of the blue at all – becoming more and more common, it seems. Sometimes quite useful, apparently….

Describing a situation in words is tricky. It transpires that a photo can be more effective and efficient than a thousand spoken words, where relevant. That long term Fitbit user showing the point at which their Blood Pressure started to change is quite useful, especially if they have been a long time user.

The consensus in any debate I’ve been in, is that opening up the health record for access offers huge possibilities for the citizen and the health service at large. At extremes, it is life saving – for example patients with congenital heart problems are in real danger if there is no access to their record and they appear at a&e out of hours with a problem. Treated at a specialist facility, the outreach of the electronic records from the specialist centre does not yet extend to every remote hospital. But patient access to their own critical data can help manage this risk. A simple PDF will do, accessible as a file in the patient portal. Same applies for those abroad, especially if they have a complex condition and have a complication – translation is even possible in this instance, based on detection of location.

With health services so stretched, sharing the care (and data entry) tasks with the citizen is surely helpful. Pre-operative assessment questionnaires? Get the patient to do it before they come in. Issue the guidance telling them to avoid that curry, or remind them to drink their two pints of water pre-CT. Every little helps. Orthopaedic follow up appointments – do remote patients really have to travel all the way if a tick box questionnaire can reveal that it’s not necessary? Why spend 42p on a stamp if you can post a letter electronically (you can even see that it’s been opened).

But we can get bogged down managing exceptions and pandering to the vocal naysayers who love to throw up exceptions for sport. The problem is, it can only take one negative reaction for the domino effect to ripple through the crowd and we’re not making progress. “My mother in law could never work a smart phone. Those that need this the most cant benefit from it”. I’ve heard this one a lot and I might have agreed had it not been for personal experiences and observations

- I watched my 2 year old working a tablet device. These devices are made to be simple, engineered through many cycles of user interface design to make them intuitive and simple to use. These devices can, of course, be tailored to support those who are less able, with enhanced fonts and locked into a simple configuration.

- My own mother in law was very anti-smart phone, she swore she’d never use one, a technophobe and I accepted that, she was one of the lost causes – we’d discussed patient access to records and she had mentioned that it would just never work for some people, it was just too complicated for that generation. How we laughed when her phone contract renewal resulted in the issue of a shiny new iPhone. She would stare at it with wide eyes, too scared to turn it on for fear of being cyber attacked and losing her life savings to a hacker.

One year on, she manages a fair amount of her activity on her iPhone and she’s got an iPad also now for her books, and for face-timing her family in Australia. She’s in a number of what’s app groups, and has a Facebook account. She doesn’t “get” twitter, that is a #stretchtoofar, but she uses the maps, train-times, flight planners and several other apps and services. There was an initial sausage fingers reaction to the unusual keypad, it was a difficult first few clicks, but this resolved quickly.

As a software supplier, whilst we’ve sold a number of patient access solutions to our customers, it’s only recently that we’ve seen a pick up in momentum of those trusts, boards and regions starting to properly pilot patient access. The slow momentum has largely been due to a focus on building the clinical record as an enabling foundation, but the tanker is starting to turn. So the next time you find yourself in a patient access debate. If you find yourself pulling an objection from your holster for the sport of the debate then my challenge to you is to pause for thought, and try instead to focus on the positive. Acceptance will come if we collectively act as champions for access to our record and the benefits for us as health service users, and to the health economy as a whole, really do need to be embraced.