Across healthcare, technology is often used to remedy systemic issues such as inefficiencies, staff shortages, and poor patient outcomes. But here’s the uncomfortable truth: poorly implemented technology can do more harm than good. It can introduce new risks, mask underlying problems, and even contribute to missed or delayed diagnoses.

The False Start: When technology disrupts more than it helps.

We’ve all witnessed the pattern: a new digital system is launched with great fanfare, only to be met with clinician frustration, workarounds, and a wave of “alert fatigue.” Rather than solving problems, these rollouts often:

- Disrupt clinical workflows

- Fracture communication

- Undermine the clinician-patient relationship

So we must ask, what if the real diagnosis is missed, not by the clinician, but by the system surrounding them?

Designing for people, not just technology.

The issue isn’t that technology can’t help. It’s that we too often design for the technology, not the people using it. Systems are frequently deployed without fully understanding the clinical environments they’re entering.

This disconnect between IT and clinical teams leads to solutions that fail to reflect real-world workflows, which costs money and contributes to burnout and reduced quality of care.

Source: Unertl et al., JAMIA Open (2020)

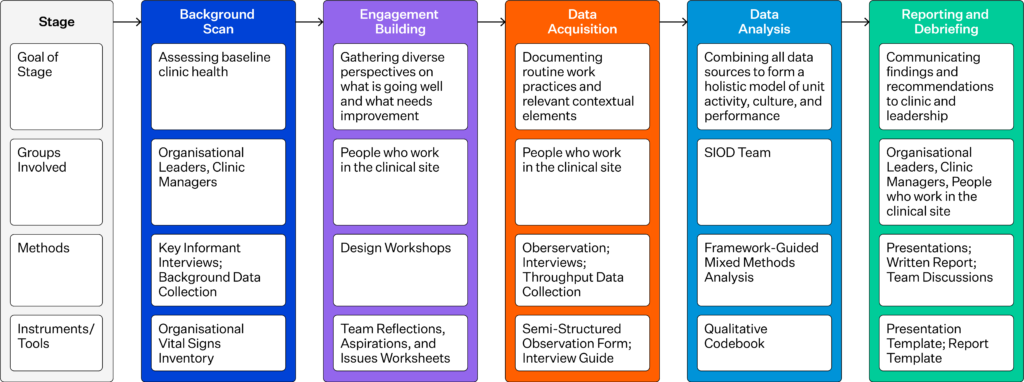

This graph highlights how SIOD helps uncover and address misalignments between technology and clinical practice through systematic, collaborative diagnostics.

True integration is iterative, not plug-and-play.

Effective tech integration is never seamless from day one. It’s iterative, messy, and inherently collaborative. According to the literature, successful integration depends on understanding three key states:

- Current state – how clinicians actually work (not just what’s written in policy)

- Future state – how the workflow should function once the tech is in place

- Gap closure – what changes in roles, processes, or tools are needed to bridge the two

Beyond interfaces: embracing human-centred redesign.

This isn’t just about user-friendly interfaces or slick software. It’s about human-centred redesign. Co-designing solutions with clinicians, aligning technical rollouts with clinical goals, and managing change in ways that build trust and shared ownership.

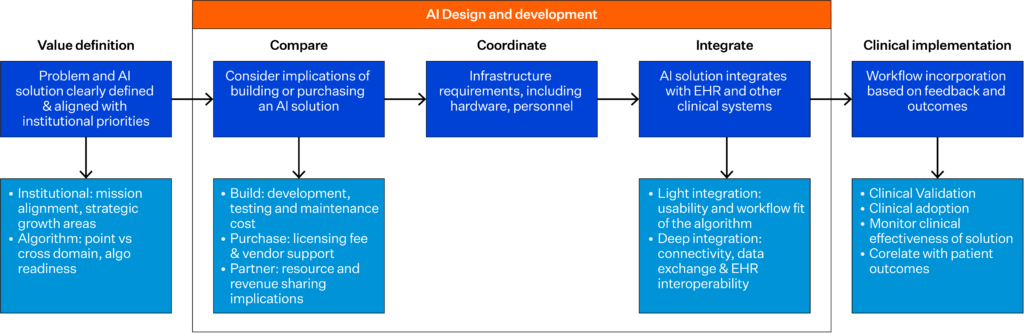

This process chart illustrates the stages institutions must work through when integrating AI into clinical workflows, emphasising decision points where clinical alignment is critical.

Diagnosis, decision-making, and the cost of getting it wrong.

At its core, this is a conversation about diagnosis. Missed or delayed diagnoses are often system failures. Technology should enhance diagnostic accuracy, not impede it.

Yet in rushed implementations, decision support tools, for example, can create noise instead of clarity, and rigid digital workflows can box clinicians into cognitive shortcuts that lead to error.

Ask better questions and solve the right problems.

To achieve true transformation, we need to stop rushing to implement technology and instead start asking better clinical questions:

- How does this technology improve the quality of care?

- Does it reduce the cognitive burden on clinicians or increase it?

- Are we solving the right problem or just digitising a broken process?

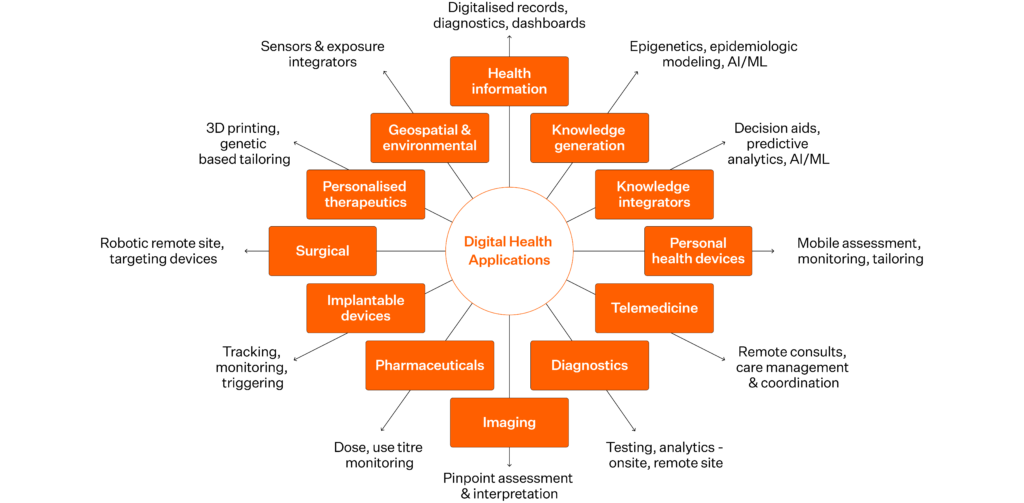

Source: National Academy of Medicine. 2019. Digital Health Action Collaborative, NAM Leadership Consortium: Collaboration for a Value & Science-Driven Health System.

Reclaiming the promise of technology in healthcare.

Digital transformation in healthcare must be grounded in clinical realities. That means:

- Involving clinical voices at every stage of the journey. The people who use the systems must help shape them.

- Committing to long-term optimisation, not just “go-lives”

- Protecting space for clinical judgment, empathy, and human connection

These are the very things technology should enable, not erode.

Let’s stop assuming technology is the answer.

Instead, let’s ensure we’re asking the right questions. The goal isn’t to deploy more tech; it’s to create systems that truly enhance diagnosis, decision-making, and the clinician-patient relationship.